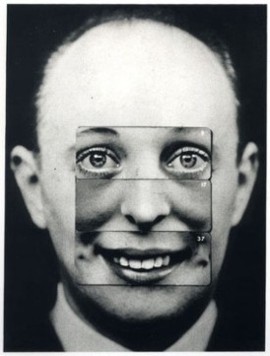

Erica Baum - Mr. 5 17 37 (2004)

1. “To this day, the “author” remains an open question…”

2. “Beckett supplies a direction: “What matter who’s speaking, someone said, what matter who’s speaking.” . . . [Writing] as an ongoing process [that] slights our customary attention to the finished product . . . [The] writing of our day has freed itself from the necessity of expression”; it only refers to itself, yet it is not restricted to the confines of interiority. On the contrary, we recognise it in its exterior deployment. This reversal transforms writing into an interplay of signs, regulated less by the content it signifies than by the very nature of the signifier. Moreover, it implies an action that is always testing the limits of its regularity, transgressing and reversing an order that it accepts and manipulates. Writing unfolds like a game that inevitably moves beyond its own rules and finally leaves them behind. Thus, the essential basis of this writing is not the exalted emotions related to the act of composition or the insertion of the subject into language. Rather, it is primarily concerned with creating an opening where the writing subject endlessly disappears.”

3. “Writing is now linked to sacrifice and to the sacrifice of life itself; it is a voluntary obliteration of the self that does not require representation in books because it takes place in the everyday existence of the writer. Where a work had the duty of creating immortality, it now attains the right to kill, to become the murderer of its author. . . If we wish to know the writer in our day, it will be through the singularity of his absence and in his links to death, which has transformed him into a victim of his own writing.”

4. “It is obviously insufficient to repeat empty slogans: the author has disappeared; God and man died a common death. Rather, we should re-examine the empty space left by the author’s disappearance; we should attentively observe, along its gaps and fault lines, its new demarcations, and the reapportionment of this void; we should await the fluid functions released by this disappearance.”

5. “Yet - and it is here that the specific difficulties attending the author’s name appear - the link between a proper name and the individual being named and the link between an author’s name and that which it names are not isomorphous and do not function in the same way; and these differences require clarification . . .

Its presence is functional in that it serves as a means of classification. A name can group together a number of texts and thus differentiate them from others. A name also establishes different forms of relationship among texts . . . Finally, the author’s name characterises a particular manner of existence of discourse. Discourse that possesses an author’s name is not to be immediately consumed and forgotten; neither is it accorded the momentary attention given to ordinary, fleeting words. Rather, this status and its manner of reception are regulated by the culture in which it circulates.

We can conclude that, unlike a proper name, which moves from the interior of a discourse to the real person outside who produced it, the name of the author, defining their form, and characterising their mode of existence. It points to the existence of certain groups of discourse and refers to the status of this discourse within a society and culture. The author’s name is not a function of a man’s civil status, nor is it fictional; it is situated in the breach, among the discontinuities, which give rise to new groups of discourse and their singular mode of existence. Consequently, we can say that in our culture, the name of the author is a variable that accompanies only certain texts to the exclusion of others . . . In this sense, the function of an author is to characterise the existence, circulation, and operation of certain discourses within society.”

6. “In dealing with the “author” as a function of discourse, we must consider the characteristics of a discourse that support this use and determine its difference from other discourses.

First, they are the objects of appropriation; the form of property they have become is of a particular type whose legal codification was accomplished some years ago.

Secondly, the “author-function” is not universal or constant in all discourse.

The third point concerning this “author-function” is that it is not formed spontaneously through the simple attribution of an individual. It results from a complex operation whose purpose is to construct the rational entity we can call an author. Undoubtedly, this construction is assigned a “realistic” dimension as we speak of an individual’s “profundity” or “creative” power, his intentions or the original inspiration manifested in the writing. Nevertheless, these aspects of an individual, which we designate as an author (or which comprise an individual as an author), are projections, in terms always more or less psychological, of our way of handling texts: in the comparisons we make, the traits we extract as pertinent, the continuities we assign, or the exclusions we practice. In addition, all these operations vary according to the period and the form of discourse concerned.”

7. “The author explains the presence of certain events within a text, as well as their transformations, distortions, and their various modifications (and this through an author’s biography or by reference to his particular point of view, in the analysis of his social preferences and his position within a class or by delineating his fundamental objectives). The author also constitutes a principle of unity in writing where any unevenness of production is ascribed to changes caused by evolution, maturation, or outside influence. In addition, the author serves to neutralise the contradictions that are found in a series of texts. Governing this function is the belief that there must be - at a particular level of an author’s thought, of his conscious or unconscious desire - a point where contradictions are resolved, where the incompatible elements can be shown to relate to one another or to cohere around a fundamental; and originating contradiction. Finally, the author is a particular sources of expression who, in more or less finished forms, is manifested equally well, and with similar validity, in a text, in letters, fragments, drafts, and so forth.”

8. “However, it would be false to consider the function of the author as a pure and simple reconstruction after the fact of a text given as passive material, since a text always bears a number of signs that refer to the author. . .

[All] discourse that supports this “author-function” is characterised by this plurality of egos.”

9. [The] “author-function” is tied to the legal and institutional systems that circumscribe, determine, and articulate the realm of discourses; it does not operate in a uniform manner in all discourses, at all times, and in any given culture; it is not defined by the spontaneous attribution of a text to its creator, but through a series of precise and complex procedures; it does not refer, purely and simply, to an actual individual insofar as it simultaneously gives rise to a variety of egos and to a series of subjective positions that individuals of any class may come to occupy.”

10. “[There] undoubtedly exist specific discursive properties or relationships that are irreducible to the rules of grammar and logic and to the laws that govern objects. These properties require investigation if we hope to distinguish the larger categories of discourse. The different forms of relationship (or nonrelationships) that an author can assume are evidently one of these discursive properties.

This form of investigation might also permit the introduction of an historical analysis of discourse. Perhaps the time has come to study not only the expressive value and formal transformations of discourse, but its mode of existence: the modifications and variations, within any culture, of modes of circulation, valorisation, attribution and appropriation. Partially at the expense of themes and concepts that an author places in his work, the “author-function” could also reveal the manner in which discourse is articulated on the basis of social relationships.

Is it not possible to re-examine, as a legitimate extension of this kind of analysis, the privileges of the subject? Clearly, in undertaking an internal and architectonic analysis of a work (whether it be a literary text, a philosophical system, or a scientific work) and in delimiting psychological and biographical references, suspicions arise concerning the absolute nature and creative role of the subject. But the subject should not be entirely abandoned. It should be reconsidered, not to restore the theme of an originating subject, but to seize its functions, its interventions in discourse, and its system of dependencies. We should suspend the typical questions: how does a free subject penetrate the density of things and endow them with meaning; how does it accomplish its design by animating the rules of discourse from within? Rather, we should ask: under what conditions and through what forms can an entity like the subject appear in the course of discourse; what position does it occupy; what functions does it exhibit; and what rules does it follow in each type of discourse? In short, the subject (and its substitutes) must be stripped of its creative role and analysed as a complex and variable function of discourse.

The author - or what I have called the “author-function” - is undoubtedly only one of the possible specifications of the subject and, considering past historical transformations, it appears that the form, complexity, and even the existence of this function are far from immutable. We can easily imagine a culture where discourse would circulate without any need for an author. Discourses, whatever their status, form, or value, and regardless of our manner of handling them, would unfold in a pervasive anonymity.”

From What is an Author? by Michel Foucault.