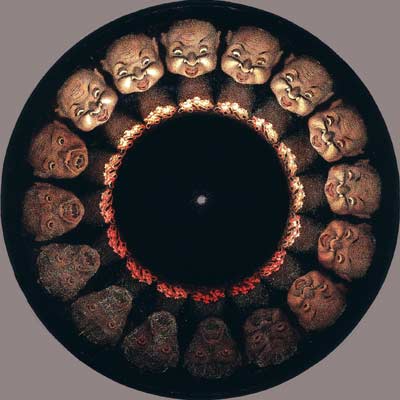

Phenakistiscope (19th Century) from the Joseph Plateau Collection

"In the medieval Christian tradition, the devil is a mimic, an actor, a performance artist, and he imitates the wonders of nature and the divine work of creation. Unlike God, he can only conjure visions as illusions, as he did when, in the person of Mephistopheles, he summoned the pageant of the deadly sins for Doctor Faustus and then seduced him with the appearance of Helen of Troy.

The Devil summons images in the mind's eye, playing on desires and weaknesses; the word "illusion" comes from ludere, "to play" in Latin. Conjurers mimic his tricks: an early Christian Father, denouncing magicians, gives a vivid account of the lamps and mirrors or basins of water they used, how they even conjured the stars by sticking fish scales or the skins of sea horses to the ceiling.

From the first showings of magic lantern slides, optical illusions were ascribed to the Devil's mischief. In the mid-17th century, when the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher began experimenting with shadows, lenses and reflections, he made images of devils with pitchforks, Mister Death brandishing his scythe, a soul burning in purgatory and other supernatural scenes, as if the new technology inevitably involved phantasms and spectres.

Optical illusions are not supernatural, however, as Kircher was intent on demonstrating through his experiments. But illusions also kept disrupting the boundaries between reality and fantasy. Demonstrating tricks of perception, especially through the use of mirrors (the art of catoptrics), Kircher showed how he could manipulate the natural properties of light and play on the limits of human faculties to create seductive and wonderful delusions.

Running through the history of magic and the anxiety that it stirred runs a parallel history of optics: if the Devil was able to conjure appearances whereas God truly performed prodigies, it was imperative to establish the truth status of the vision.

The collection that Werner Nekes has made over the past 30 years, displayed in the coming Hayward Gallery exhibition Eyes, Lies and Illusion, gives a fascinating insight into the enchanted enigma of appearances, and into the history of optical investigation into these mysteries. It's a rich repository of human thought about vision and all that it implies, and it includes the whole range of optical devices, playing with every kind of effect, from supernatural apparitions to visual puns and cracker fillers, from the highest accomplishments of human intelligence to the most light-hearted eye-twisters or visual jokes. His assorted wonders of instruments, images, machines, toys, illusions and effects span more than four centuries of human ingenuity and invention at its most lively, ranging from an exquisite prism said to have belonged to the philosopher Blaise Pascal to an 1898 automated flip book-cum-peepshow of a female dancer dimpling and flirting.

"The soul never thinks without a mental image," declared Aristotle. Trying to enhance human physical capacities with lenses and apparatus of various kinds has been a strong motive behind optical inventions. But the desire to reproduce mental imagining has been an equally powerful engine behind inquiries into the working of eye and brain. Robert Fludd, an Oxford philosopher and esoteric neoplatonist of the generation before Kircher, imagined the "eye of the imagination" as a prototype film projector, beaming images on to a screen floating in virtual space, somewhere at the back of the eyes. Descartes declared, "First, it is the soul that sees, not the eye...", and this primacy of the imagination offered some explanation for dreams and visions and apparitions.

In the field of optics, many instruments were created to analyse and reproduce vision, such as the camera lucida, the lens of which projects a reflected image onto the artist's paper or canvas. But optics also reflects ideas about consciousness at any given period; it expresses the potential of the inward eye for every generation, the concepts of cognition and mental projection, and the tendency of the mind to assemble random marks into intelligible data.

In 1784, the landscape painter Alexander Cozens advised fellow artists to follow the promptings of fantasy and create images from blots of ink on crumpled paper: this astonishingly modern idea about chance and composition echoed Leonardo da Vinci's practice, nearly three centuries earlier. Leonardo was in fact quoting his fellow artist, Botticelli: "By merely throwing a sponge full of diverse colours at a wall, it left a stain on that wall, where a fine landscape was seen." But Cozens arrived at his "New Method" on his own, without prior knowledge of his Renaissance precursors, and made startlingly expressionist images. Werner Nekes has a rare album of 1885 filled with drawings of imps and devils that were doodled by workmen following the drips and splashes of coffee on the walls they were plastering.

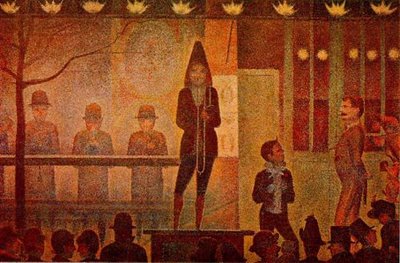

Anxiety about the unreliability of vision continued long after most believers in the Devil's antics had faded away, and after the 17th century it spurred closer analysis of the human faculties, especially sight. These discoveries led to the society of surveillance on the one hand, and of mass media on the other. But it is also the case that new technologies created a mass of popular illusions that no longer alarmed their consumers, but amused them hugely. These were diversions and spectacles, and they were pure pleasure.

In 1827, John Ayrton Paris created the thaumatrope (from Greek "wonder" combined with "motion"), a round disc threaded on a string with one picture on one side and another on the reverse; when the disc was spun, the images merged. The thaumatrope was crucial to the development of moving pictures, which would eventually give the impression of life itself flowing past when projected on to a screen at the rate of 24 frames a second. Phantasmagoria shows began touring Europe at the end of the 18th century. In the wake of the Terror in France, the brilliant impresario, balloonist and cinematic pioneer Etienne-Gaspard Robertson inaugurated the thrills of the horror movies when he projected spectres on to smoke - including the severed head of Danton, then a recent victim of the guillotine.

The Victorian audience was travelling vicariously in the footsteps of explorers who continued to open up continents: the natural magic of the lantern slide beamed natural wonders from all round the world. Many different kinds of shows revealed worlds near and far through spectacular illusions. In 1821, in order to make a panoramic painting of London, the Hull-born artist Thomas Hornor climbed to the top of the cross on the dome of St Paul's Cathedral, and built a crow's nest. From here, where Hornor bivouacked for the time it took, he made a 360-degree picture of London. He used a telescope to examine details, and calculated the perspective to position the viewer convincingly in the scene.

In Edinburgh in 1835, Maria Theresa Short, daughter of an optical instrument maker, created one of the very first popular public camera obscuras. It is still there, on Castle Hill, and it captures through a periscope and angled lenses the thronged scenes of the streets below, projected by light rays alone onto a white convex dish. The projection is still an astonishing effect, and it brings into being, with no more magic than a series of angled lenses, ancient dreams of summoning absent sights through gazing into a bowl of water or an oracular mirror.

Optical media of communication available today have opened paths to new forms of beauty in reflection and projection, distortion and illusion. When Tony Oursler, on display in the exhibition, projects lopsided spectral faces uttering messages from the ether, or angels ascend through streaming water in Bill Viola's films, or Gary Hill materialises eerie apparitions that loom and then fade, they are claiming this territory for art in our era, and pressing optics into the service of a new metaphysics.

The taming of illusion through deeper understanding and ever more ingenious techniques of simulation has only been partial. There has remained something stubbornly weird about the images optical devices can create, especially with the advent of cinema when they became so clever at producing the appearance of the real.

Werner Nekes's collection plays a range of effects as if on a giant organ of visual phenomena, from profound investment in the objective truth of vision to an equally strong engagement with radical subjectivity. However, as we move nearer our era, his artefacts and devices reveal how the media of visual trickery, deception and illusion move away from scientific scrutiny towards distraction, leisure and entertainment. At the same time, the perfection of visual technologies has destabilised experience until we cannot be sure if we are not the dreamers but the dreamed, as in a recursive fable by Jorge Luis Borges. On television in the US, footage sometimes carries the heading "Metaphorical Images" to warn that the film does not communicate what is actually occurring. As The Matrix films dramatise, illusion has turned us into wanderers in "the desert of the real".

The world accessible to the senses began to fall away a very long time ago, perhaps in Plato's cave; it began turning into an insubstantial pageant of optical illusion, placing the observer in the dislocating yet oddly pleasurable situation of not knowing where reality begins and ends."

Marina Warner,

The Guardian, Saturday September 25, 2004

Note: Eyes, Lies & Illusions, drawn from the Werner Nekes collection - and based on an exhibition originally devised by the Hayward Gallery, South Bank Centre, London - is now on show at at ACMI (Australian Centre for the Moving Image) until 11 February 2007.